- Home

- Counseling and Know-how

- Knowledge Machine

Strevent argues that at the root of the Scientific Revolution is the recognition of what he calls the “iron rule of explanation” in all its leniency (shallow explanatory power of theories) and brutality (no arguments should appear in official publications, thus leaving aside theology, philosophy, aesthetics, and all that is not directly linked to empirical evidence and its theoretical prediction; this proscription makes the rule “irrational”). It is Isaac Newton the author who first embodied the Revolution, as he was practicing with the same intensity multiple tracks of knowledge (as it was recommended till then from ancient times) yet keeping them separated not only in public but also in his mind. The fact that this became accepted may be an outcome of the 30-year was, which made the custom of separating public and private personae common and accepted (to avoid new wars). With time, this compartmentalization has stuck, and has become the norm also because on the one hand philosophy has been denigrated and on the other proto-scientists are more and more educated to become insensitive to anything cultural that could distract them from the hard discipline of science. Concerning the latter, Strevens acknowledges Kuhn’s remark that scientists need something to believe and be engaged with so that they can dedicate their life to uncovering the minutiae of the subject matter (Tychonic principle), which would hardly happen otherwise, and therefore claims that C. P. Snow has it paradoxically wrong in calling for a reunion of humanities with science (though he arguably is all for it; the book is reach in notes (unfortunately not at the foot of pages) and bibliographic apparatus, by the way). Strevens also does not agree with Kuhn on the blinding power of the paradigm on actual scientists, nor on the explanatory relativism that is attached to the idea (incommensurability of paradigms, in Kuhn’s words). Strevens also criticizes Popper’s falsificationism as it is practically impossible to implement given the theoretical cohorts and plausibility rankings that are de facto attached to any theory, and that are largely ambiguous and thus subjective. Still, the iron rule incorporates the need to reject theories whose predictions do not match empirical facts, as well as the gradual (Baconian) convergence of a community into agreement towards a theory given the capacity to account for an ever-larger amount of data, and the acknowledgment of leaving free private space for the individual’s idiosyncrasies, that is the domain of radical subjectivists (Feyerabend to start with). Thus Strevens solves the Great Method Debate in his opinion. Strevens concludes that Science has to leave space for scientists to fight within the hard constraints of the sterilizing iron rule and that Science needs to be left alone (he promises a follow-up book).

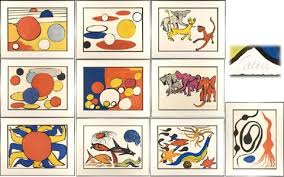

This is a great read – crystal clear writing, polished and concise; polite and forceful arguments, respectful and critical; illustrated with illuminating anecdotes and historical excursi as well as nice pictures.