- Home

- Counseling and Know-how

- Antifragile: Things that gain ...

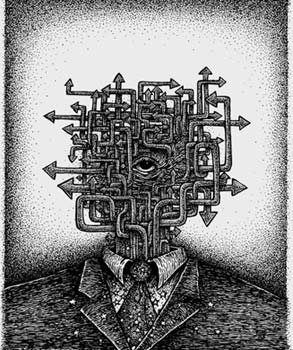

In his previous two divulgative essays Taleb was descriptive: he showed his views on the world out there, where randomness plays a role much larger than commonly thought and extreme, unpredictable events shape the landscape of things to come. With Antifragile, Taleb turns prescriptive: he brings the news that the nature of the world is not something from which to only hide and protect, or at best being robust against, but rather something from which to take advantage is as well possible given the correct exposure. To Taleb the opposite of fragile in not robust, rather something that takes benefice from randomness to improve, strengthen, reinforce, grow, mature. This is what he calls the antifragile for a lack of better word — in fact, he claims such concept was roughly intuited along history by some philosophers, yet no word in no common language has come to identify this state of things. People confound antifragility with (robustness and) resilience, but a book that increases its selling count because of bad reviews or prohibitions is more than robust.

The book is repleted with inversions of cause and effects much in the vein of his previous aphoristic pamphlet, and sees the author proposing many ideas as direct derivation or extrapolation of a basic empiric evidence: randomness hurts the fragile, leaves stable the robust but enhance the antifragile. The root of the antifragile is a nonlinear, positively convex-exposure to randomness, so that eventual minor losses of bounded entity can be compensated by rarer but possibly unbounded gains. Related to this are the concepts of asymmetry in choices and actual probability distributions; the practical superiority of tinkering and heuristics to theories (echoing the ludic fallacy); how to be able to thrive in a world that one does not understand (nor should claim to do) by using optionality (which implies the use of rationality) rather than intelligence (time as the ultimate filter and tester of fragility), the preference to detection of fragility (which can be quantified) rather than to prediction of events (which uses models and mistakes models for reality, and is necessary only when the system to be protected is implicitly fragile); the dangers of iatrogenics (naive interventionism and agency problem, as opposed to action by subtraction, that is, via negativa). As usual, the host of ideas is put on the plate with an aphoristic flavor and decorated by autobiographical episodes, proclaims of sincerity and relentless attacks on economists, academics and Fragilistas in general (those who claim to understand how things work and act consequently). He converges to a single ethical rule, the same foreseen by Hammurabi: no action without skin in the game — people who only express opinions without being in the position of possible loss due to those opinions are to be considered charlatans. Taleb finds them all over the place, particularly protected by corporations and societies and by huge premium bonuses. He is intolerant of the big and likes the organic; he warns against big data as an intoxicating source of noise and errors, destined to raise much faster than the actual information thereby contained (as the possible but non-necessarily meaningful correlations between multivariate distributions). He also warns against neomania, or the search for the new for the sake of it, in spite of the Lindy effect that intrinsically warns against it; and condemns touristification as one big problem of modernity, namely the vacuuming of natural randomness and lively bounded tumult from aspects of life (modern specialization is in fact possible only in artificially smoothened domains). He proclaims to instruct his life with barbell strategies, where middle ground is excluded and rather a conservative behavior with minimal exposure is balanced with a minor part of extreme risk which may eventually lead to unprecedented gains (he sees hormesis as an organic precursor to antifragility).

Taleb’s writing style is a deluge. He just writes what he really wants and when he wants, so that the text exudes a spontaneous feel, tumultuous but still interconnected, a disciplined swirl of ideas, parables, anecdotes, digressions and technicalities without ever loosing sight of erudite references and reminders to the old masters. His predilection for amateurs in all fields (that is, non-professional players of arts and crafts) is inspiring (besides reaching home here). It is indeed somehow remarkable that he is able to expand on his findings so much — he claims to spend most of his time in is private library or dwelling as a flaneur in bars and libraries — and still retain a certain unity in his narrative. One can still spot some contradiction: for instance, he claims to believe only in people that tell what to not do, yet he is prescribing conducts in many fields (not lastly in medicine, where iatrogenics is first spotted); and, as recurrent, he talks mostly about distributions of general events but indulges in singular anecdotes (which is correct only when dealing with large deviations and Black Swans indeed). And one needs to have a taste for or at least go along with his fierceness and severe judgments. This given, the book is provocative and supported enough to be inspiring and eventually illuminating, if only to expand the philosophical jargon with a new, useful concept. Then one can argue whether Taleb is mostly defending his own way of life — just like many philosophers end up tailoring their arguments to make space for their prejudices and customary habits. Still the spectacle his highly enjoyable and makes for a refreshing and nourishing read. Finally, the book provides technical appendices to support the vulgar versions of the arguments with theorems; and in barbell style is coupled to a thick, freely-downloadable technical companion online.